-40%

Native American 6" Long Stone Wedge to Fell Trees. Kalapuya Tribe, Oregon. AACA

$ 129.35

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

Houghton USAAncient Art, Antiques, & Fine

Collectibles

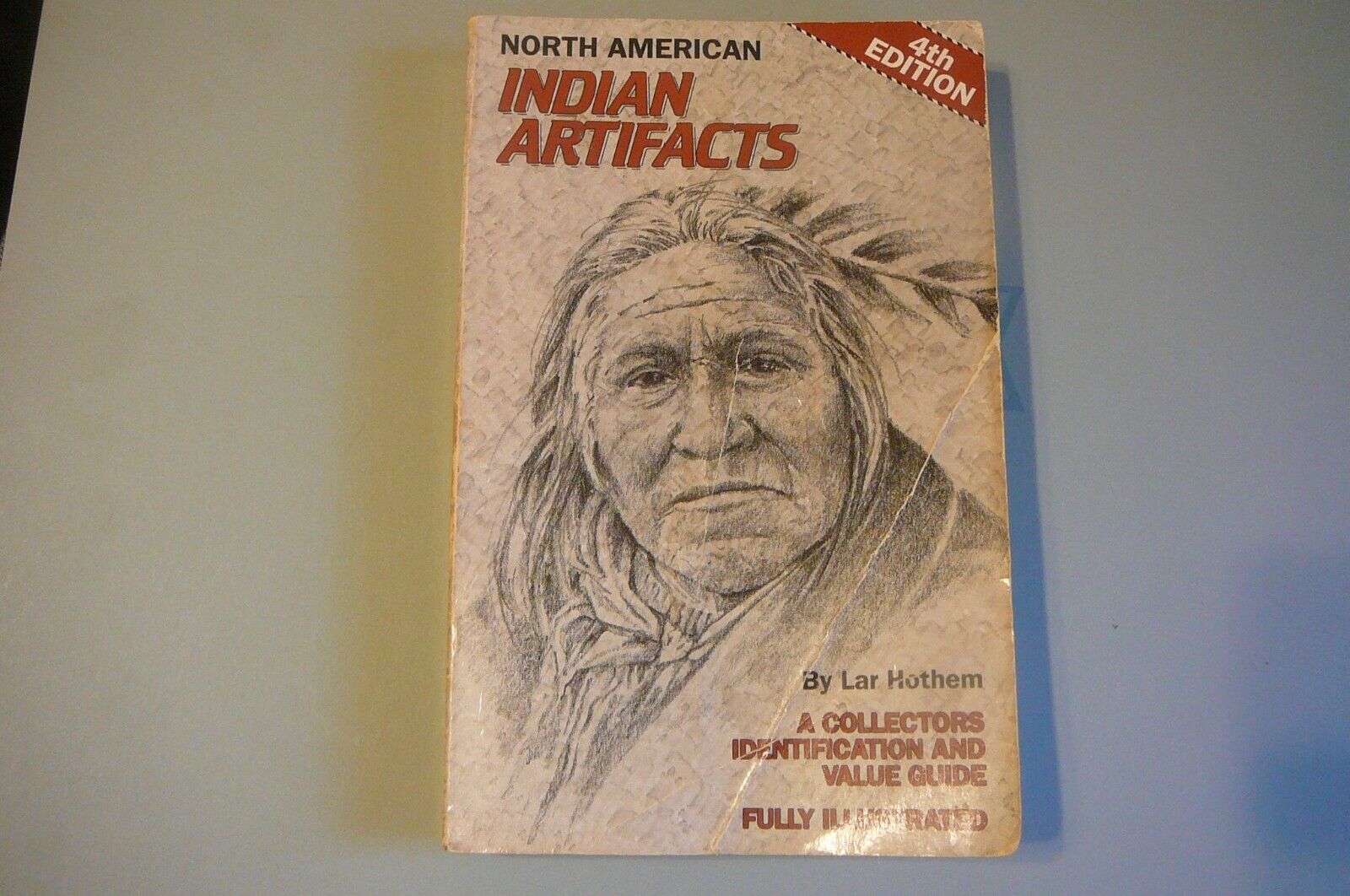

Native American Kalapuya People Stone Wedge

Ancient Tool Used to Fell Trees Using Fire

Willamette Valley, Oregon

eBay Note

I certify that this item was legally collected on private land with the owner's permission during the 20th century.

This is an opportunity to legally own an ancient, Native American artifact that is estimated to be about 200 years-old!

This rectangular stone wedge was made by the Kalapuya People of Oregon centuries ago.

It is about 5.95” long x 1.35” wide x 1.71” deep and weighs 1.17 lbs.

It has four flat sides and one end that shows clear impact chips caused by repeated hits with a stone maul.

Native Americans of the Santiam band of the Kalapuya in Oregon made this stone wedge of dark granite.

It has a scorched, blackened appearance and still retains the burnt smell from fire that was likely caused when it was used along with fire set at the base of large cedar trees to fell them.

{NOTE:

The Yamhill Kalapuya People had a tribal center called

Chachalu

, which translates to "place of the burnt timbers"; a massive forest fire burned through the Grand Ronde Valley shortly before the time of Relocation in 1856. It is possible that the burnt residue on this wedge came from that fire.}

These stone wedges were carefully chosen for their hardness, shape, and resistance to cracking or chipping.

They could be easily grasped in one hand and hit with a stone maul with the other hand.

Southern Indians used just the hand maul, but the Northern Nations used the heavy hafted maul—a maul with a handle. Many of these stones were sculpted to resemble the users' spirit helper in a form of an animal or bird.

The Northwest Coastal Indian had several ways of felling their trees. One method was by burning the base of the trunk. The feller would set red-hot rocks inside a chiseled-out cavity to burn the wood. Under direction, workers, often slaves, then chiseled and adzed out the charred pieces and used stone wedges to force the tree over. A similar technique was to set the fire to the base of the tree and then use wet clay to prevent the rest of it from catching fire.

Some wedges made of wood, elk bone or elk antler, would have been driven into a Northwest cedar tree after it was cut down to split the log into long, thick planks that were used to build sturdy planked houses centuries ago.

To split the cedar into planks, which could be used for building houses or boxes, a small cut was made in the log. Wedges of bone or antler were then inserted into the cut and pounded in with a maul. Using wedges of graded sizes, the log was then split into planks.

These wedges are much more common than this stone wedge.

PROVENANCE/HISTORY

Sometime deep in the past several century ago or more, a member of the

Santiam band of the Kalapuya

people stopped on small hill near the Willamette River to trade items with other tribes NW tribes—this wedge was found with dozens of other trade items.

Today, the Kalapuya People are part of the 30 tribes and bands from western Oregon, northern California, and southwest Washington that make up the recognized and incorporated into the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon.

This amazing Northwest tool was a surface find years ago from an ancient, Indian trading camp & surrounding smaller camps on the banks of where the two Willamette rivers meet in Springfield, Oregon.

This location is near the base of Mount Pisgah, which natives and travelers considered to be sacred ground

Starting about 200 years ago, Native Americans would trade with European settlers in the region for iron metal wedges that were even more durable.

So, we can surmise that this stone wedge is at least 200 years old and likely much older.

These stone tools tell a piece of a story about large, prosperous tribes engaging in long distance trade for specialty items.

It’s a far different story than the one written by the white settlers who came to the Willamette Valley on the Oregon trail.

By then epidemics had killed virtually all the Kalapuya people. In just a few generations, about 95 percent of the native population in the Willamette Valley died.

Felling Trees with Fire and Stone Wedges

As a result of working with this versatile cedar for thousands of years, generations of Native Americans in the Northwest devised and perfected various technologies for felling and transporting trees. They were also quite equipped at splitting and cutting planks, joining pieces of wood together, steaming and bending wood, and sanding finished products. They could also easily patch and repair their damaged objects.

Since the cedar tree played such a large role in the Northwest Indian’s survival, the trees played a large role in their tribes' economy.

Wealthy families laid claim to good stands of cedar near the waters. A family without such rights had to pay the owner for the privilege to cut and use his trees. Because of this high demand, specialists offered their services for a high profit. Some specialists would go and live with the family that was hiring his services. These specialists became so knowledgeable and skilled in using the cedar that they would even harvest at specific times of the year to avoid the trees' sap.

It was also important to find the right tree for a specific purpose.

There were many functions for the use of trees, such as house construction, canoe building, and mortuary poles. A canoe maker would ritually fast and pray to properly choose the right tree. The darker the forest was, the fewer limbs and knot holes, because trees had to grow quickly to fight for the sun.

For the best trees, one would look in the darker parts of the forest, hoping to find one not too far from a river, but on occasion, trees were cut several kilometers inland. Before felling a tree, the man in charge respectfully addressed the spirit of the tree with a prayer asking for the trunk to topple in the direction he wished. The person would calculate the direction so that the cedar’s fall would be cushioned by hitting other trees on its way down.

This would prevent the trunk from cracking.

The Northwest Coastal Indian had several ways of felling their trees. One method was by burning the base of the trunk. The feller would set red-hot rocks inside a chiseled-out cavity to burn the wood. Under direction, workers, often slaves, then chiseled and adzed out the charred pieces. A similar technique was to set the fire to the base of the tree and then use wet clay to prevent the rest of it from catching fire.

Another method was to use scaffolding and a platform around the trunk and then chisel two parallel grooves 12" apart around the trunk. Then they used wedges and stone mauls to split out the wood from between the grooves. They would repeat this process again and again until the tree fell.

Only a chief who owned many slaves would attempt to fell very large cedar. The felling of trees was slow and tedious, generally taking two to three days to cut down a large one, therefore, the cost would be quite high and would require a lot of wealth and power to take on such a feat.

Once the tree was felled the people would remove the top of it by the same burning and chiseling method, then they would adze off the bark and sapwood. If the wood was for a canoe, they might hollow it out first before removing it from the forest.

Removing a log from the forest was an extremely difficult task. Men would pull with cedar ropes attached to the log, men would push, and others would use long poles to pry at the log. In all, it took around two hundred men a total of twenty-four hours to get the log to water.

After the log was in the water it was pulled by several canoes to the village. People would then beach the log at high tide and proceed to trim and shape it. If used for a house, two to three hundred men and women would pull the log up the slope to the construction site. Some logs used in these homes ranged up to forty-five feet long and three feet in diameter.

Please examine the attached photos carefully as they are part of the description and bid accordingly.

Ruler is NOT part of the sale.

Note:

Each object I sell is professionally researched and compared with similar objects in the collections of the finest museums in the world.

I have been dealing in fine antiquities for almost 50 years and although certainly not an expert in every field, I have been honored to appraise, buy, collect, and enjoy and recently sell some of the finest ancient art in the world.

When in doubt, I have worked with dozens of subject matter experts to determine the condition and authenticity of numerous antiquities and antiques.

This documentation helps to insure you are buying quality items and helps to protect your investment.

Please ask any questions you may have

before

you bid!

All sales are Final, unless I have seriously misrepresented this item!

Please look at the macro photos carefully as they are part of the description.

Member of the Authentic Artifact Collectors Association (AACA) & the Archaeological Institute of America (AIA)

Per e-Bay's rules,

PayPal

only please!

FREE USA SHIPPING includes insurance and is accurate for all 50 States!